The reason behind Meta's last move

My theory behind Meta’s cookie paywall

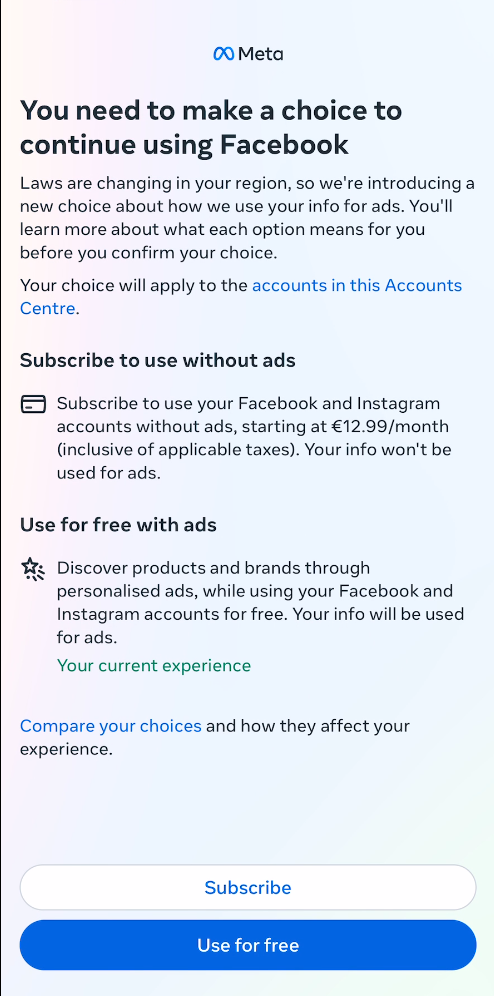

Meta announced around a month ago that they were planning on making people pay to use their services (Facebook and Instagram), or rather leave their users with a choice between either consenting to all personal data collection or paying a substantial fee (’€9.99/month on the web or €12.99/month on iOS and Android’).

So good for the ‘Facebook is free and always will be’, right?

But why are they doing that? No one is fooled, people are not gonna pay to continue watching cat videos on Instagram, so what is the actual reason behind this move, this alleged change in their business model?

Unmet legal requirements

It arguably boils down from requirements specified in the GDPR when it comes to consent – which has to be informed, unambiguous, specific, etc –, and for lawful processing of data overall. Meta doesn’t meet these requirements when it comes to behavior-based marketing according to the Norwegian DPA, Datatilsynet (sorry for the Google link). Datatilsynet banned Meta’s practices in Norway, and recently instructed the Irish DPA (in charge of Meta because their EU HQ is in Dublin) to extend the ban to all of the EU. It resulted in the EDPB (European Data Protection Board) issuing an Urgent Binding Decision.

Meta knew what was coming, they knew all along. What they are trying to achieve here is to buy some time by going into a grey zone: the cookie paywall uncertainty legal jungle. But what is a cookie paywall? And what do I mean by uncertainty legal jungle?

Cookie paywalls

As we analysed with my co-authors in a paper last year and in another one this year, some websites started to use a new species of consent notices which we coined cookie paywalls. The idea is to leave users with a choice between either consenting to all personal data collection or paying a fee, otherwise they can’t access the website visited (hence the wall).

Does it remind you of something? Yes, it’s the exact same technique Meta is rolling. And guess what? Barely 1/1000 users pay when facing such a notice.

But we haven’t touched the why they are doing this.

It should be fine if no one agrees, right?

In the conclusions of both our papers, we highlight the lack of harmonization between the EU member states. This lack of harmonization is what I call uncertainty legal jungle: indeed, how can you fine a company if state A says “it’s OK”, while state B claims “it’s not”, state C “it depends”, and states D to Z have not issued anything on it anyway? So when Meta claims that ’the CJEU expressly recognised that a subscription model, like the one we are announcing, is a valid form of consent’, they’re not exactly telling the truth, they’re presenting one aspect of it, the facet that goes nicely with their story.

Meta saw this lack of harmonized legal field as an opportunity, a way out of the upcoming quagmire caused by the Norwegian decision, and decided to breached in. They could have continued to provide ads without personalization, but tracking is their business model.

Business as usual, ?

That’s my theory behind Meta’s last move: they want to claim legal compliance to conduct business as usual. While what’s actually happening is that they’re taking advantage of this uncertainty, and definitely not changing anything to their business model: no one will pay anyway.

So one last question with lots of implications: what do we do now?

Because one thing remains very unclear: are we sure that Meta, I mean Zuckerberg’s company – formerly Facebook –, will actually respect people’s choices? I would not bet on this one without extremely solid guarantees which I doubt they would be able to provide. And even if they do respect our choices and not track us if we pay, how many are gonna pay?

Can transparency make Meta better? They have been doing a decent job at explaining why people see ads, but transparency without control is not empowerment. At any rate, that’s a requirement but not a sufficient one: seeing your privacy violated doesn’t make it unviolated.

I am no economist, so take what I say with a pinch of salt, but I think we need to see more radical changes. Banning surveillance-based advertising can be one. Addressing the concentration of power big tech companies (such as Meta) have is another.

With more confidence and expertise, I can say that it might be time to ban cookie paywalls, at least regulate this practice in a concerted way. Indeed, monetizing a human right doesn’t sound like an appealing future to me.